I’m in the middle of an identity crisis. For 5 years beginning in 2011, I was sick with an diagnosed autoimmune thyroid disorder. For 5 years, by the end of the day, I was not the person I was in the morning. I battled sleepless nights, anxiety, memory loss, unshakable weight gain and the most incredible lethargy. I would wake up at 9 am; by 11 am, it was a struggle to stay awake until bedtime when I couldn’t really sleep well. It became so normal that I just assumed that most people couldn’t stay awake for the entirety of the day but had to find their own triggers to keep them alert. It sounds silly. But it is important to stress that for 3 years, my GP insisted that I needed to learn how to deal with stress better. I was convinced by my doctor that I was battling stress. By my last visit with him in 2014, he looked me in the eye and said ‘Stop playing a victim. There is nothing wrong with you.” I never saw him or any doctor again until 29 August 2016.

During those diagnosed years, I would make awesome plans with my friends out of excitement. By the time the hour arrived, I would cancel 80% of the commitments. My body was unable to keep up with my spirit. There were very few friends who stood by me at the end of it. I too struggled to understand how this party animal turned into a perpetual flake. The month I was diagnosed, I was sleeping up 16 hours a day. By the time I got dressed and made it to the door, I could no longer remember where I was going.

Being sick for 7 years has changed me. I have been on hormone replacement therapy for 2 years and I will be for life. Whilst it has monumentally changed my life, there are things that I have to do every day that I didn’t have to prior to 2011. I vaguely remember the carefree, outgoing person I used to be. Even when that girl decides to come out, I have to stick to a disciplined lifestyle in order to maintain my good health. I can’t pull regular all nighters anymore. There are no more cheeky Tuesday drinks. There is no more bread or gluten. No more over exertion. No more intense 15-hour work binges. No more long drives. No. Those things thrust me back into my sick zone. My sustained wellbeing requires that I ensure that I do not overwhelm myself for a prolonged period, which for me even 24 hours of poor planning can set me back 2 weeks.

So that brings me to my identity crisis. I am trying to figure out who I am now. All of my activities: my professional life, personal life, philanthropy have taken a backseat to monitoring my health and preventing a relapse. I have accepted that this is going to be my reality for the rest of my life.

Who am I as an academic? To this day, I don’t know how I completed my thesis, but I did. And I have a 3-year contract job now. And it’s another part of my life that I now have to balance with my health.

Naturally, I’ve decided to read my way through this crisis. So the point… is every week I’m going to read a book about perseverance and attempt to blog about it. I tend to keep most of my writing in my notebooks but I am trying to engage more online.

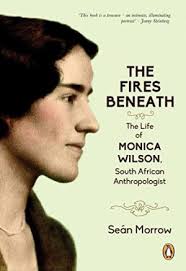

I decided to read ‘The fires beneath: The life of Monica Wilson, South African anthropologist‘. My dad gave it to me as she was quite influential in anthropological fieldwork.

I’ll be back next week with a review.